Illustration by Michael Houtz

The euthanasia conference was held at a Sheraton. Some 300 Canadian professionals, most of them clinicians, had arrived for the annual event. There were lunch buffets and complimentary tote bags; attendees could look forward to a Friday-night social outing, with a DJ, at an event space above Par-Tee Putt in downtown Vancouver. “The most important thing,” one doctor told me, “is the networking.”

Which is to say that it might have been any other convention in Canada. Over the past decade, practitioners of euthanasia have become as familiar as orthodontists or plastic surgeons are with the mundane rituals of lanyards and drink tickets and It’s been so long s outside the ballroom of a four-star hotel. The difference is that, 10 years ago, what many of the attendees here do for work would have been considered homicide.

When Canada’s Parliament in 2016 legalized the practice of euthanasia—Medical Assistance in Dying, or MAID, as it’s formally called—it launched an open-ended medical experiment. One day, administering a lethal injection to a patient was against the law; the next, it was as legitimate as a tonsillectomy, but often with less of a wait. MAID now accounts for about one in 20 deaths in Canada—more than Alzheimer’s and diabetes combined—surpassing countries where assisted dying has been legal for far longer.

It is too soon to call euthanasia a lifestyle option in Canada, but from the outset it has proved a case study in momentum. MAID began as a practice limited to gravely ill patients who were already at the end of life. The law was then expanded to include people who were suffering from serious medical conditions but not facing imminent death. In two years, MAID will be made available to those suffering only from mental illness. Parliament has also recommended granting access to minors.

At the center of the world’s fastest-growing euthanasia regime is the concept of patient autonomy. Honoring a patient’s wishes is of course a core value in medicine. But here it has become paramount, allowing Canada’s MAID advocates to push for expansion in terms that brook no argument, refracted through the language of equality, access, and compassion. As Canada contends with ever-evolving claims on the right to die, the demand for euthanasia has begun to outstrip the capacity of clinicians to provide it.

There have been unintended consequences: Some Canadians who cannot afford to manage their illness have sought doctors to end their life. In certain situations, clinicians have faced impossible ethical dilemmas. At the same time, medical professionals who decided early on to reorient their career toward assisted death no longer feel compelled to tiptoe around the full, energetic extent of their devotion to MAID. Some clinicians in Canada have euthanized hundreds of patients.

The two-day conference in Vancouver was sponsored by a professional group called the Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers. Stefanie Green, a physician on Vancouver Island and one of the organization’s founders, told me how her decades as a maternity doctor had helped equip her for this new chapter in her career. In both fields, she explained, she was guiding a patient through an “essentially natural event”—the emotional and medical choreography “of the most important days in their life.” She continued the analogy: “I thought, Well, one is like delivering life into the world, and the other feels like transitioning and delivering life out.” And so Green does not refer to her MAID deaths only as “provisions”—the term for euthanasia that most clinicians have adopted. She also calls them “deliveries.”

Gord Gubitz, a neurologist from Nova Scotia, told me that people often ask him about the “stress” and “trauma” and “strife” of his work as a MAID provider. Isn’t it so emotionally draining? In fact, for him it is just the opposite. He finds euthanasia to be “energizing”—the “most meaningful work” of his career. “It’s a happy sad, right?” he explained. “It’s really sad that you were in so much pain. It is sad that your family is racked with grief. But we’re so happy you got what you wanted.”

[From the June 2023 issue: David Brooks on how Canada’s assisted-suicide law went wrong]

Has Canada itself gotten what it wanted? Nine years after the legalization of assisted death, Canada’s leaders seem to regard MAID from a strange, almost anthropological remove: as if the future of euthanasia is no more within their control than the laws of physics; as if continued expansion is not a reality the government is choosing so much as conceding. This is the story of an ideology in motion, of what happens when a nation enshrines a right before reckoning with the totality of its logic. If autonomy in death is sacrosanct, is there anyone who shouldn’t be helped to die?

Rishad Usmani remembers the first patient he killed. She was 77 years old and a former Ice Capades skater, and she had severe spinal stenosis. Usmani, the woman’s family physician on Vancouver Island, had tried to talk her out of the decision to die. He would always do that, he told me, when patients first asked about medically assisted death, because often what he found was that people simply wanted to be comfortable, to have their pain controlled; that when they reckoned, really reckoned, with the finality of it all, they realized they didn’t actually want euthanasia. But this patient was sure: She was suffering, not just from the pain but from the pain medication too. She wanted to die.

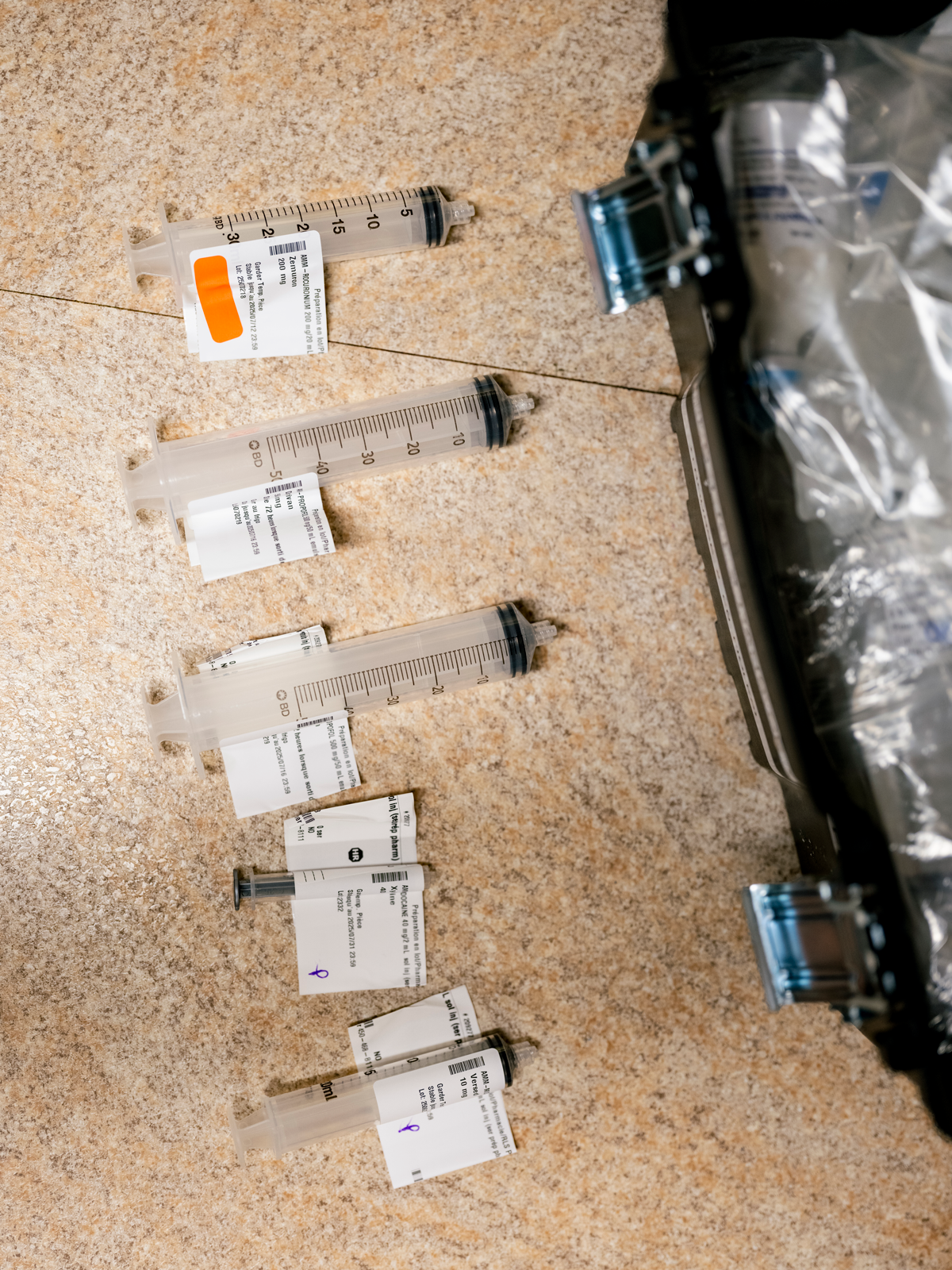

On December 13, 2018, Usmani arrived at the woman’s home in the town of Comox, British Columbia. He was joined by a more senior physician, who would supervise the procedure, and a nurse, who would start the intravenous line. The patient lay in a hospital bed, her sister next to her, holding her hand. Usmani asked her a final time if she was sure; she said she was. He administered 10 milligrams of midazolam, a fast-acting sedative, then 40 milligrams of lidocaine to numb the vein in preparation for the 1,000 milligrams of propofol, which would induce a deep coma. Finally he injected 200 milligrams of a paralytic agent called rocuronium, which would bring an end to breathing, ultimately causing the heart to stop.

Usmani drew his stethoscope to the woman’s chest and listened. To his quiet alarm, he could hear the heart still beating. In fact, as the seconds passed, it seemed to be quickening. He glanced at his supervisor. Where had he messed up? But as soon as they locked eyes, he understood: He was listening to his own heartbeat.

Many clinicians in Canada who have provided medical assistance in dying have a story like this, about the tangle of nerves and uncertainties that attended their first case. Death itself is something every clinician knows intimately, the grief and pallor and paperwork of it. To work in medicine is to step each day into the worst days of other people’s lives. But approaching death as a procedure, as something to be scheduled over Outlook, took some getting used to. In Canada, it is no longer a novel and remarkable event. As of 2023, the last year for which data are available, some 60,300 Canadians had been legally helped to their death by clinicians. In Quebec, more than 7 percent of all deaths are by euthanasia—the highest rate of any jurisdiction in the world. “I have two or three provisions every week now, and it’s continuing to go up every year,” Claude Rivard, a family doctor in suburban Montreal, told me.

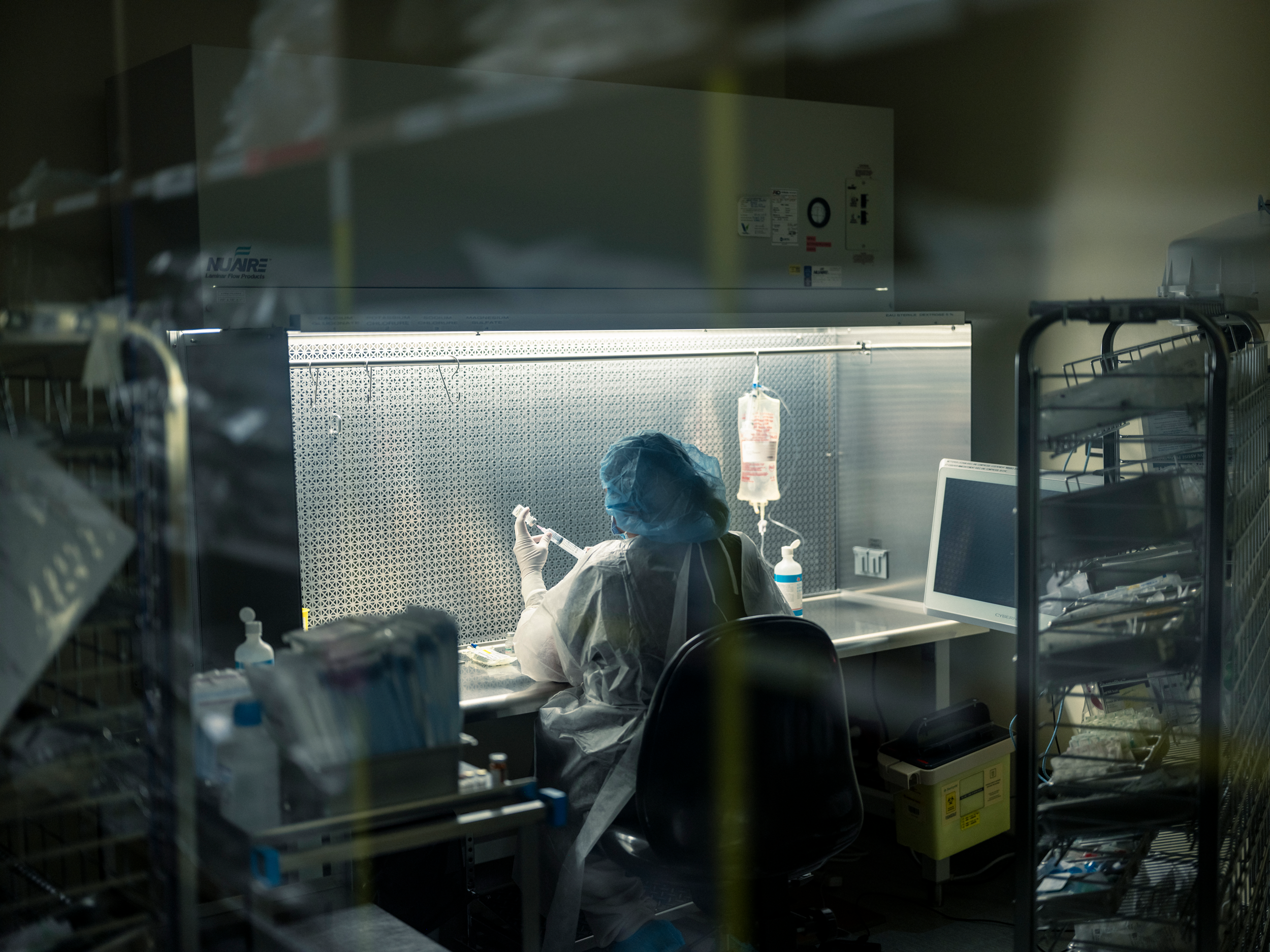

Rivard has thus far provided for more than 600 patients and helps train clinicians new to MAID. This spring, I watched from the back of a small classroom in a Vancouver hospital as Rivard led a workshop on intraosseous infusion—administering drugs directly into the bone marrow, a useful skill for MAID clinicians, Rivard explained, in the event of IV failure. Arranged on absorbent pads across the back row of tables were eight pig knuckles, bulbous and pink. After a PowerPoint presentation, the dozen or so attendees took turns with different injection devices, from the primitive (manual needles) to the modern (bone-injection guns). Hands cramped around hollow steel needles as the workshop attendees struggled to twist and drive the tools home. This was the last thing, the clinicians later agreed, that patients would want to see as they lay trying to die. Practitioners needed to learn. “Every detail matters,” Rivard told the class; he preferred the bone-injection gun himself.

The details of the assisted-death experience have become a preoccupation of Canadian life. Patients meticulously orchestrate their final moments, planning celebrations around them: weekend house parties before a Sunday-night euthanasia in the garden; a Catholic priest to deliver last rites; extended-family renditions of “Auld Lang Syne” at the bedside. For $10.99, you can design your MAID experience with the help of the Be Ceremonial app; suggested rituals include a story altar, a forgiveness ceremony, and the collecting of tears from witnesses. On the Disrupting Death podcast, hosted by an educator and a social worker in Ontario, guests share ideas on subjects such as normalizing the MAID process for children facing the death of an adult in their life—a pajama party at a funeral home; painting a coffin in a schoolyard.

Autonomy, choice, control: These are the values that found purchase with the great majority of Canadians in February 2015, when, in a case spearheaded by the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association, the supreme court of Canada unanimously overturned the country’s criminal ban on medically assisted death. For advocates, the victory had been decades in the making—the culmination of a campaign that had grown in fervor since the 1990s, when Canada’s high court narrowly ruled against physician-assisted death in a case brought by a patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS. “We’re talking about a competent person making a choice about their death,” one longtime right-to-die activist said while celebrating the new ruling. “Don’t access this choice if you don’t want—but stay away from my death bed.” A year later, in June 2016, Parliament passed the first legislation officially permitting medical assistance in dying for eligible adults, placing Canada among the handful of countries (including Belgium, Switzerland, and the Netherlands) and U.S. states (Oregon, Vermont, and California, among others) that already allowed some version of the practice.

[Read: How do I make sense of my mother’s decision to die?]

The new law approved medical assistance in dying for adults who had a “grievous and irremediable medical condition” causing them “intolerable suffering,” and who faced a “reasonably foreseeable” natural death. To qualify, patients needed two clinicians to sign off on their application, and the law required a 10-day “reflection period” before the procedure could take place. Patients could choose to die either by euthanasia—having a clinician administer the drugs directly—or, alternatively, by assisted suicide, in which a patient self-administers a lethal prescription orally. (Virtually all MAID deaths in Canada have been by euthanasia.) When the procedure was set to begin, patients were required to give final consent.

The law, in other words, was premised on the concept of patient autonomy, but within narrow boundaries. Rather than force someone with, say, late-stage cancer to suffer to the very end, MAID would allow patients to depart on their own terms: to experience a “dignified death,” as proponents called it. That the threshold of eligibility for MAID would be high—and stringent—was presented to the public as self-evident, although the criteria themselves were vague when you looked closely. For instance, what constituted “reasonably foreseeable”? Two months? Two years? Canada’s Department of Justice suggested only “a period of time that is not too remote.”

Provincial health authorities were left to fill in the blanks. Following the law’s passage, doctors, nurse practitioners, pharmacists, and lawyers scrambled to draw up the regulatory fine print for a procedure that until then had been legally classified as culpable homicide. How should the assessment process work? What drugs should be used? Particularly vexing was the question of whether it should be clinicians or patients who initiated conversations about assisted death. Some argued that doctors and nurses had a professional obligation to broach the subject of MAID with potentially eligible patients, just as they would any other “treatment option.” Others feared that patients could interpret this as a recommendation—indeed, feared that talking about assisted death as a medical treatment, like Lasik surgery or a hip replacement, was dangerous in itself.

Early on, a number of health-care professionals refused to engage in any way with MAID—some because of religious beliefs, and others because, in their view, it violated a medical duty to “do no harm.” For many clinicians, the ethical and logistical challenges of MAID only compounded the stress of working within Canada’s public-health-care system, beset by years of funding cuts and staffing shortages. The median wait time for general surgery is about 22 weeks. For orthopedic surgery, it’s more than a year. For some kinds of mental-health services, the wait time can be longer.

As the first assessment requests trickled in, even many clinicians who believed strongly in the right to an assisted death were reluctant to do the actual assisting. Some told me they agreed to take on patients only after realizing that no one else—in their hospital or even their region—was willing to go first. Matt Kutcher, a physician on Prince Edward Island, was more open to MAID than others, but acknowledged the challenge of building the practice of assisted death virtually from scratch. “The reality,” he said, “is that we were all just kind of making it up as we went along, very cautiously.”

On a rainy spring evening in 2017, Kutcher drove to a farmhouse by the sea to administer the first state-sanctioned act of euthanasia in his province. The patient, Paul Couvrette, had learned about MAID from his wife, Liana Brittain, in 2015, soon after the supreme-court decision. He had just been diagnosed with lung cancer, and while processing this fact in the parking lot of the clinic had turned to his wife and announced: “I’m not going to have cancer. I’m going to kill myself.” Brittain told her husband this was a bit dramatic. “You know, dear, you don’t have to do that,” she recalls responding. “The government will do it for you, and they’ll do it for free.” Couvrette had marveled at the news, because although he was open to surgery, he had no interest in chemotherapy or radiation. MAID, Brittain told me, gave her husband the relief of a “back door.” By early 2017, the cancer had spread to Couvrette’s brain; the 72-year-old became largely bedridden. He set his MAID procedure for May 10—the couple’s wedding anniversary.

Kutcher and a nurse had agreed to come early and join the extended family—children, a granddaughter—for Couvrette’s final dinner: seafood chowder and gluten-free biscuits. Only Brittain would eventually join Couvrette in the downstairs bedroom; the rest of the family and the couple’s two dogs would wait outside on the beach. There was a shared understanding, Kutcher recalled, that “this was something none of us had experienced before, and we didn’t really know what we were in for.” What followed was a “beautiful death”—that was what the local newspaper called it, Brittain told me. Couvrette’s last words to his wife came from their wedding vows: I’ll love you forever, plus three days.

Kutcher wrestled at first with the sheer strangeness of the experience—how quickly it was over, packing up his equipment at the side of a dead man who just 10 minutes earlier had been talking with him, very much alive. But he went home believing he had done the right thing for his patient.

For proponents, Couvrette epitomized the ideal MAID candidate, motivated not by an impulsive death wish but by a considered desire to reclaim control of his fate from a terminal disease. The lobbying group Dying With Dignity Canada celebrated Couvrette’s “empowering choice and journey” as part of a showcase on its website of “good deaths” made possible by the new law. There was also the surgeon in Nova Scotia with Parkinson’s who “died the same way he lived—on his own terms.” And there were the Toronto couple in their 90s who, in a “dream ending to their storybook romance,” underwent MAID together.

Such heartfelt accounts tended to center on the white, educated, financially stable patients who represented the typical MAID recipient. The stories did not precisely capture what many clinicians were discovering also to be true: that if dying by MAID was dying with dignity, some deaths felt considerably more dignified than others. Not everyone has coastal homes or children and grandchildren who can gather in love and solidarity. This was made clear to Sandy Buchman, a palliative-care physician in Toronto, during one of his early MAID cases, when a patient, “all alone,” gave final consent from a mattress on the floor of a rental apartment. Buchman recalls having to kneel next to the mattress in the otherwise empty space to administer the drugs. “It was horrible,” he told me. “You can see how challenging, how awful, things can be.”

In 2018, Buchman co-founded a nonprofit organization called MAiDHouse. The aim was to create a “third place” of sorts for people who want to die somewhere other than a hospital or at home. Finding a location proved difficult; many landlords were resistant. But by 2022, MAiDHouse had leased the space in Toronto from which it operates today. (For security reasons, the location is not public.) Tekla Hendrickson, the executive director of MAiDHouse, told me the space was designed to feel warm and familiar but also adaptable to the wishes of the person using it: furniture light enough to rearrange, bare surfaces for flowers or photos or any other personal items. “Sometimes they have champagne, sometimes they come in limos, sometimes they wear ball gowns,” Hendrickson said. The act of euthanasia itself takes place in a La-Z-Boy-like recliner, with adjacent rooms available for family and friends who may prefer not to witness the procedure. According to the MAiDHouse website, the body is then transferred to a funeral home by attendants who arrive in unmarked cars and depart “discreetly.”

Since its founding, MAiDHouse has provided space and support for more than 100 deaths. The group’s homepage displays a photograph of dandelion seeds scattering in a gentle wind. A second MAiDHouse location recently opened in Victoria, British Columbia. In the organization’s 2023 annual report, the chair of the board noted that MAiDHouse’s followers on LinkedIn had increased by 85 percent; its new Instagram profile was gaining followers too. More to the point, the number of provisions performed at MAiDHouse had doubled over the previous year—“astounding progress for such a young organization.”

In the early days of MAID, some clinicians found themselves at once surprised and conflicted by the fulfillment they experienced in helping people die. A few months after the law’s passage, Stefanie Green, whom I’d met at the conference in Vancouver, acknowledged to herself how “upbeat” she’d felt following a recent provision—“a little hyped up on adrenaline,” as she later put it in a memoir about her first year providing medical assistance in death. Green realized it was gratification she was feeling: A patient had come to her in immense pain, and she had been in a position to offer relief. In the end, she believed, she had “given a gift to a dying man.”

Green had at first been reluctant to reveal her feelings to anyone, afraid that she might be viewed, she recalled, as a “psychopath.” But she did eventually confide in a small group of fellow MAID practitioners. Green and several colleagues realized that there was a need for a formal community of professionals. In 2017, they officially launched the group whose meeting I attended.

There was a time when Madeline Li would have felt perfectly at home among the other clinicians who convened that weekend at the Sheraton. In the early years of MAID, few physicians exerted more influence over the new regime than Li. The Toronto-based cancer psychiatrist led the development of the MAID program at the University Health Network, the largest teaching-hospital system in Canada, and in 2017 saw her framework published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

It was not long into her practice, however, that Li’s confidence in the direction of her country’s MAID program began to falter. For all of her expertise, not even Li was sure what to do about a patient in his 30s whom she encountered in 2018.

The man had gone to the emergency room complaining of excruciating pain and was eventually diagnosed with cancer. The prognosis was good, a surgeon assured him, with a 65 percent chance of a cure. But the man said he didn’t want treatment; he wanted MAID. Startled, the surgeon referred him to a medical oncologist to discuss chemo; perhaps the man just didn’t want surgery. The patient proceeded to tell the medical oncologist that he didn’t want treatment of any kind; he wanted MAID. He said the same thing to a radiation oncologist, a palliative-care physician, and a psychiatrist, before finally complaining to the patient-relations department that the hospital was barring his access to MAID. Li arranged to meet with him.

Canada’s MAID law defines a “grievous and irremediable medical condition” in part as a “serious and incurable illness, disease, or disability.” As for what constitutes incurability, however, the law says nothing—and of the various textual ambiguities that caused anxiety for clinicians early on, this one ranked near the top. Did “incurable” mean a lack of any available treatment? Did it mean the likelihood of an available treatment not working? Prominent MAID advocates put forth what soon became the predominant interpretation: A medical condition was incurable if it could not be cured by means acceptable to the patient.

This had made sense to Li. If an elderly woman with chronic myelogenous leukemia had no wish to endure a highly toxic course of chemo and radiation, why should she be compelled to? But here was a young man with a likely curable cancer who nevertheless was adamant about dying. “I mean, he was so, so clear,” Li told me. “I talked to him about What if you had a 100 percent chance? Would you want treatment? And he said no.” He didn’t want to suffer through the treatment or the side effects, he explained; just having a colonoscopy had traumatized him. When Li assured the man that they could treat the side effects, he said she wasn’t understanding him: Yes, they could give him medication for the pain, but then he would have to first experience the pain. He didn’t want to experience the pain.

What was Li left with? According to prevailing standards, the man’s refusal to attempt treatment rendered his disease incurable and his natural death was reasonably foreseeable. He met the eligibility criteria as Li understood them. But the whole thing seemed wrong to her. Seeking advice, she described the basics of the case in a private email group for MAID practitioners under the heading “Eligible, but Reasonable?” “And what was very clear to me from the replies I got,” Li told me, “is that many people have no ethical or clinical qualms about this—that it’s all about a patient’s autonomy, and if a patient wants this, it’s not up to us to judge. We should provide.”

And so she did. She regretted her decision almost as soon as the man’s heart stopped beating. “What I’ve learned since is: Eligible doesn’t mean you should provide MAID,” Li told me. “You can be eligible because the law is so full of holes, but that doesn’t mean it clinically makes sense.” Li no longer interprets “incurable” as at the sole discretion of the patient. The problem, she feels, is that the law permits such a wide spectrum of interpretations to begin with. Many decisions about life and death turn on the personal values of practitioners and patients rather than on any objective medical criteria.

By 2020, Li had overseen hundreds of MAID cases, about 95 percent of which were “very straightforward,” she said. They involved people who had terminal conditions and wanted the same control in death as they’d enjoyed in life. It was the 5 percent that worried her—not just the young man, but vulnerable people more generally, whom the safeguards had possibly failed. Patients whose only “terminal condition,” really, was age. Li recalled an especially divisive early case for her team involving an elderly woman who’d fractured her hip. She understood that the rest of her life would mean becoming only weaker and enduring more falls, and she “just wasn’t going to have it.” The woman was approved for MAID on the basis of frailty.

Li had tried to understand the assessor’s reasoning. According to an actuarial table, the woman, given her age and medical circumstances, had a life expectancy of five or six more years. But what if the woman had been slightly younger and the number was closer to eight years—would the clinician have approved her then? “And they said, well, they weren’t sure, and that’s my point,” Li explained. “There’s no standard here; it’s just kind of up to you.” The concept of a “completed life, or being tired of life,” as sufficient for MAID is “controversial in Europe and theoretically not legal in Canada,” Li said. “But the truth is, it is legal in Canada. It always has been, and it’s happening in these frailty cases.”

Li supports medical assistance in dying when appropriate. What troubles her is the federal government’s deferring of responsibility in managing it—establishing principles, setting standards, enforcing boundaries. She believes most physicians in Canada share her “muddy middle” position. But that position, she said, is also “the most silent.”

In 2014, when the question of medically assisted death had come before Canada’s supreme court, Etienne Montero, a civil-law professor and at the time the president of the European Institute of Bioethics, warned in testimony that the practice of euthanasia, once legal, was impossible to control. Montero had been retained by the attorney general of Canada to discuss the experience of assisted death in Belgium—how a regime that had begun with “extremely strict” criteria had steadily evolved, through loose interpretations and lax enforcement, to accommodate many of the very patients it had once pledged to protect. When a patient’s autonomy is paramount, Montero argued, expansion is inevitable: “Sooner or later, a patient’s repeated wish will take precedence over strict statutory conditions.” In the end, the Canadian justices were unmoved; Belgium’s “permissive” system, they contended, was the “product of a very different medico-legal culture” and therefore offered “little insight into how a Canadian regime might operate.” In a sense, this was correct: It took Belgium more than 20 years to reach an assisted-death rate of 3 percent. Canada needed only five.

In retrospect, the expansion of MAID would seem to have been inevitable; Justin Trudeau, then Canada’s prime minister, said as much back in 2016, when he called his country’s newly passed MAID law “a big first step” in what would be an “evolution.” Five years later, in March 2021, the government enacted a new two-track system of eligibility, relaxing existing safeguards and extending MAID to a broader swath of Canadians. Patients approved for an assisted death under Track 1, as it was now called—meaning the original end-of-life context—were no longer required to wait 10 days before receiving MAID; they could die on the day of approval. Track 2, meanwhile, legalized MAID for adults whose deaths were not reasonably foreseeable—people suffering from chronic pain, for example, or from certain neurological disorders. Although cost savings have never been mentioned as an explicit rationale for expansion, the parliamentary budget office anticipated annual savings in health-care costs of nearly $150 million as a result of the expanded MAID regime.

The 2021 law did provide for additional safeguards unique to Track 2. Assessors had to ensure that applicants gave “serious consideration”—a phrase left undefined—to “reasonable and available means” to alleviate their suffering. In addition, they had to affirm that the patients had been directed toward such options. Track 2 assessments were also required to span at least 90 days. For any MAID assessment, clinicians must be satisfied not only that a patient’s suffering is enduring and intolerable, but that it is a function of a physical medical condition rather than mental illness, say, or financial instability. Suffering is never perfectly reducible, of course—a crisp study in cause and effect. But when a patient is already dying, the role of physical disease isn’t usually a mystery, either.

Track 2 introduced a web of moral complexities and clinical demands. For many practitioners, one major new factor was the sheer amount of time required to understand why the person before them—not terminally ill—was asking, at that particular moment, to die. Clinicians would have to untangle the physical experience of chronic illness and disability from the structural inequities and mental-health struggles that often attend it. In a system where access to social supports and medical services varies so widely, this was no small challenge, and many clinicians ultimately chose not to expand their practice to include Track 2 patients.

There is no clear official data on how many clinicians are willing to take on Track 2 cases. The government’s most recent information indicates that, in 2023, out of 2,200 MAID practitioners overall, a mere 89 were responsible for about 30 percent of all Track 2 provisions. Jonathan Reggler, a family physician on Vancouver Island, is among that small group. He openly acknowledges the challenges involved in assessing Track 2 patients, as well as the basic “discomfort” that comes with ending the life of someone who is not in fact dying. “I can think of cases that I’ve dealt with where you’re really asking yourself, Why? ” he told me. “Why now? Why is it that this cluster of problems is causing you such distress where another person wouldn’t be distressed? ”

Yet Reggler feels duty bound to move beyond his personal discomfort. As he explained it, “Once you accept that people ought to have autonomy—once you accept that life is not sacred and something that can only be taken by God, a being I don’t believe in—then, if you’re in that work, some of us have to go forward and say, ‘We’ll do it.’ ”

For some MAID practitioners, however, it took encountering an eligible patient for them to realize the true extent of their unease with Track 2. One physician, who requested anonymity because he was not authorized by his hospital to speak publicly, recalled assessing a patient in their 30s with nerve damage. The pain was such that they couldn’t go outside; even the touch of a breeze would inflame it. “They had seen every kind of specialist,” he said. The patient had tried nontraditional therapies too—acupuncture, Reiki, “everything.” As the physician saw it, the patient’s condition was serious and incurable, it was causing intolerable suffering, and the suffering could not seem to be relieved. “I went through all of the tick boxes, and by the letter of the law, they clearly met the criteria for all of these things, right? That said, I felt a little bit queasy.” The patient was young, with a condition that is not terminal and is usually treatable. But “I didn’t feel it was my place to tell them no.”

He was not comfortable doing the procedure himself, however. He recalled telling the MAID office in his region, “Look, I did the assessment. The patient meets the criteria. But I just can’t—I can’t do this.” Another clinician stepped in.

In 2023, Track 2 accounted for 622 MAID deaths in Canada—just over 4 percent of cases, up from 3.5 percent in 2022. Whether the proportion continues to rise is anyone’s guess. Some argue that primary-care providers are best positioned to negotiate the complexities of Track 2 cases, given their familiarity with the patient making the request—their family situation, medical history, social circumstances. This is how assisted death is typically approached in other countries, including Belgium and the Netherlands. But in Canada, the system largely developed around the MAID coordination centers assembled in the provinces, complete with 1-800 numbers for self-referrals. The result is that MAID assessors generally have no preexisting relationship with the patients they’re assessing.

How do you navigate, then, the hidden corridors of a stranger’s suffering? Claude Rivard told me about a Track 2 patient who had called to cancel his scheduled euthanasia. As a result of a motorcycle accident, the man could not walk; now blind, he was living in a long-term-care facility and rarely had visitors; he had been persistent in his request for MAID. But when his family learned that he’d applied and been approved, they started visiting him again. “And it changed everything,” Rivard said. He was in contact with his children again. He was in contact with his ex-wife again. “He decided, ‘No, I still have pleasure in life, because the family, the kids are coming; even if I can’t see them, I can touch them, and I can talk to them, so I’m changing my mind.’ ”

I asked Rivard whether this turn of events—the apparent plasticity of the man’s desire to die—had given him pause about approving the patient for MAID in the first place. Not at all, he said. “I had no control on what the family was going to do.”

Some of the opposition to MAID in Canada is religious in character. The Catholic Church condemns euthanasia, though Church influence in Canada, as elsewhere, has waned dramatically, particularly where it was once strongest, in Quebec. But from the outset there were other concerns, chief among them the worry that assisted death, originally authorized for one class of patient, would eventually become legal for a great many others too. National disability-rights groups warned that Canadians with physical and intellectual disabilities—people whose lives were already undervalued in society, and of whom 17 percent live in poverty—would be at particular risk. As assisted death became “sanitized,” one group argued, “more and more will be encouraged to choose this option, further entrenching the ‘better off dead’ message in public consciousness.”

For these critics, the “reasonably foreseeable” death requirement had been the solitary consolation in an otherwise lost constitutional battle. The elimination of that protection with the creation of Track 2 reinforced their conviction that MAID would result in Canada’s most marginalized citizens being subtly coerced into premature death. Canadian officials acknowledged these concerns—“We know that in some places in our country, it’s easier to access MAID than it is to get a wheelchair,” Carla Qualtrough, the disability-inclusion minister, admitted in 2020—but reiterated that socioeconomic suffering was not a legal basis for MAID. Justin Trudeau took pains to assure the public that patients were not being backed into assisted death because of their inability to afford proper housing, say, or get timely access to medical care. It “simply isn’t something that ends up happening,” he said.

Sathya Dhara Kovac, of Winnipeg, knew otherwise. Before dying by MAID in 2022, at the age of 44, Kovac wrote her own obituary. She explained that life with ALS had “not been easy”; it was, as far as illnesses went, a “shitty” one. But the illness itself was not the reason she wanted to die. Kovac told the local press prior to being euthanized that she had fought unsuccessfully to get adequate home-care services; she needed more than the 55 hours a week covered by the province, couldn’t afford the cost of a private agency to take care of the balance, and didn’t want to be relegated to a long-term-care facility. “Ultimately it was not a genetic disease that took me out, it was a system,” Kovac wrote. “I could have had more time if I had more help.”

Earlier this spring, I met in Vancouver with Marcia Doherty; she was approved for Track 2 MAID shortly after it was legalized, four years ago. The 57-year-old has suffered for most of her life from complex chronic illnesses, including myalgic encephalomyelitis, fibromyalgia, and Epstein-Barr virus. Her daily experience of pain is so total that it is best captured in terms of what doesn’t hurt (the tips of her ears; sometimes the tip of her nose) as opposed to all the places that do. Yet at the core of her suffering is not only the pain itself, Doherty told me; it’s that, as the years go by, she can’t afford the cost of managing it. Only a fraction of the treatments she relies on are covered by her province’s health-care plan, and with monthly disability assistance her only consistent income, she is overwhelmed with medical debt. Doherty understands that someday, the pressure may simply become too much. “I didn’t apply for MAID because I want to be dead,” she told me. “I applied for MAID on ruthless practicality.”

It is difficult to understand MAID in such circumstances as a triumphant act of autonomy—as if the state, by facilitating death where it has failed to provide adequate resources to live, has somehow given its most vulnerable citizens the dignity of choice. In January 2024, a quadriplegic man named Normand Meunier entered a Quebec hospital with a respiratory infection; after four days confined to an emergency-room stretcher, unable to secure a proper mattress despite his partner’s pleas, he developed a painful bedsore that led him to apply for MAID. “I don’t want to be a burden,” he told Radio-Canada the day before he was euthanized, that March.

[Read: Brittany Maynard and the challenge of dying with dignity]

Nearly half of all Canadians who have died by MAID viewed themselves as a burden on family and friends. For some disabled citizens, the availability of assisted death has sowed doubt about how the medical establishment itself sees them—about whether their lives are in fact considered worthy of saving. In the fall of 2022, a 49-year-old Nova Scotia woman who is physically disabled and had recently been diagnosed with breast cancer was readying for a lifesaving mastectomy when a member of her surgical team began working through a list of pre-op questions about her medications and the last time she ate—and was she familiar with medical assistance in dying? The woman told me she felt suddenly and acutely aware of her body, the tissue-thin gown that wouldn’t close. “It left me feeling like maybe I should be second-guessing my decision,” she recalled. “It was the thing I was thinking about as I went under; when I woke up, it was the first thought in my head.” Fifteen months later, when the woman returned for a second mastectomy, she was again asked if she was aware of MAID. Today she still wonders if, were she not disabled, the question would even have been asked. Gus Grant, the registrar and CEO of the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Nova Scotia, has said that the timing of the queries to this woman was “clearly inappropriate and insensitive,” but he also emphasized that “there’s a difference between raising the topic of discussing awareness about MAID, and possible eligibility, from offering MAID.”

And yet there is also a reason why, in some countries, clinicians are either expressly prohibited or generally discouraged from initiating conversations about assisted death. However sensitively the subject is broached, death never presents itself neutrally; to regard the line between an “offer” and a simple recitation of information as somehow self-evident is to ignore this fact, as well as the power imbalance that freights a health professional’s every gesture with profound meaning. Perhaps the now-suspended Veterans Affairs caseworker who, in 2022, was found by the department to have “inappropriately raised” MAID with several service members had meant no harm. But according to testimony, one combat veteran was so shaken by the exchange—he had called seeking support for his ailments and was not suicidal, but was told that MAID was preferable to “blowing your brains out”—that he left the country.

In 2023, Kathrin Mentler, who lives with concurrent mental and physical disabilities, including rheumatoid arthritis and other forms of chronic pain, arrived at Vancouver General Hospital asking for help amid a suicidal crisis. Mentler has stated in a sworn affidavit that the hospital clinician who performed the intake told her that although they could contact the on-call psychiatrist, no beds were available in the unit. The clinician then asked if Mentler had ever considered MAID, describing it as a “peaceful” process compared with her recent suicide attempt via overdose, for which she’d been hospitalized. Mentler said that she left the hospital in a “panic,” and that the encounter had validated many of her worst fears: that she was a “burden” on an overtaxed system and that it would be “reasonable” for her to want to die. (In response to press reports about Mentler’s experience, the regional health authority said that the conversation was part of a “clinical evaluation” to assess suicide risk and that staff are required to “explore all available care options” with patients.)

MAID advocates dispute the charge that disabled Canadians are being quietly or overtly pressured to consider assisted death, calling it a myth generated by what they view as sensationalized accounts in the press; in parliamentary hearings, lawmakers, citing federal data, have emphasized that “only a small number” of MAID recipients are unable to access the medical services and social supports they require. Even so, this past March, the United Nations Committee on the Rights of Persons With Disabilities formally called for the repeal of Track 2 MAID in Canada—arguing that the federal government had “fundamentally changed” the premise of assisted dying on the basis of “negative, ableist perceptions of the quality and value” of disabled lives, without addressing the systemic inequalities that amplify their perceived suffering.

Marcia Doherty agrees that it should never have come to this: her country resolving to assist her and other disabled citizens more in death than in life. She is furious that she has been “allowed to deteriorate,” despite advocating for herself before every agency and official capable of effecting change. But she is adamantly opposed to any repeal of Track 2. She expressed a sentiment I heard from others in my reporting: that the “relief” of knowing an assisted death is available to her, should the despair become unbearable, has empowered her in the fight to live.

Doherty may someday decide to access MAID. But she doesn’t want anyone ever to say she “chose” it.

Ellen Wiebe never had reservations about taking on Track 2 cases—indeed, unlike most clinicians, she never had reservations about providing MAID at all. The Vancouver-based family physician had long been comfortable with controversy, having spent the bulk of her four decades in medicine as an abortion provider. As Wiebe saw it, MAID was perfectly in keeping with her “human-rights-focused” career. Over the past nine years, she has euthanized more than 430 patients and become one of the world’s most outspoken champions of MAID. Today, while virtually all of her colleagues rely on referrals from MAID coordination centers, Wiebe regularly receives requests directly from patients. Coordinators also call her when they have a patient whose previous MAID requests were rejected. (There is no limit to how many times a person can apply for MAID.) “Because I’m me, you know, they send those down to Ellen Wiebe,” she told me. I asked her what she meant by that. “My reputation,” she replied.

In the summer of 2024, Wiebe heard from a 53-year-old woman in Alberta who was experiencing acute psychiatric distress—“the horrors,” the patient called them—compounded by her reaction to, and then withdrawal from, an antipsychotic drug she was prescribed for sleep. None of the woman’s doctors would facilitate her desire to die. This was when, according to the version of events the woman’s common-law husband would later submit to British Columbia’s supreme court, she searched online for alternatives and came across Wiebe. At the end of their first meeting, a Zoom call, Wiebe said she would approve the woman for the procedure. On her formal application, the woman gave “akathisia”—a movement disorder characterized by intense feelings of inner restlessness and an inability to sit still, commonly caused by withdrawal from antipsychotic medication—as her reason for requesting an assisted death. According to court filings, no one the woman knew was willing to witness her sign the application form, as the law requires, so Wiebe had a volunteer at her clinic do so over Zoom. And because the woman still needed another physician or nurse practitioner to declare her eligible, Wiebe arranged for Elizabeth Whynot, a fellow family physician in Vancouver, to provide the second assessment. The patient was approved for MAID after a video call, and the procedure was set for October 27, 2024, in Wiebe’s clinic.

Following the approval, detailed in the court filings, the Alberta woman had another Zoom call with Wiebe; this time, her husband joined the conversation. He had concerns, specifically as to how akathisia qualified as “irremediable.” Specialists had assured the woman that if she committed to the gradual tapering protocol they’d prescribed, she could very likely expect relief within months. The husband also worried that Wiebe hadn’t sufficiently considered his wife’s unresolved mental-health issues, and whether she was capable, in her present state, of giving truly informed consent. The day before his wife was scheduled to die, he petitioned a Vancouver judge to halt the procedure, arguing that Wiebe had negligently approved the woman on the basis of a condition that did not qualify for MAID. In a widely publicized decision, the next morning the judge issued a last-minute injunction blocking Wiebe or any other clinician from carrying out the woman’s death as scheduled. “I can only imagine the pain she has been experiencing, and I recognize that this injunction will likely only make that worse,” the judge wrote. But there was an “arguable case,” he concluded, as to whether the criteria for MAID had been “properly applied in the circumstances.” The husband did not seek a new injunction after the temporary order expired, and in January, he withdrew the lawsuit altogether. Wiebe would not comment on the case other than to say she has never violated MAID laws and does not know of any provider who has. The lawyer who had represented the husband said she could not comment on whether the woman is still alive.

A number of similar lawsuits have been filed in recent years as Canadians come to terms with the hollow oversight of MAID. Because no formal procedure exists for challenging an approval in advance of a provision, many concerned family members see little choice but to take a loved one to court to try to halt a scheduled death. What oversight does exist takes place at the provincial or territorial level, and only after the fact. Protocols differ significantly across jurisdictions. In Ontario, the chief coroner’s office oversees a system in which all Track 2 cases are automatically referred to a multidisciplinary committee for postmortem scrutiny. Since 2018, the coroner’s office has identified more than 480 compliance issues involving federal and provincial MAID policies, including clinicians failing to consult with an expert in their patient’s condition prior to approval—a key Track 2 safeguard—and using the wrong drugs in a provision. The office’s death-review committee periodically publishes summaries of particular cases, for both Track 1 and Track 2, to “generate discussion” for “practical improvement.”

There was, for example, the case of Mr. C, a man in his 70s who, in 2024, requested MAID while receiving in-hospital palliative care for metastatic cancer. It should have been a straightforward Track 1 case. But two days after his request, according to the committee’s report, the man experienced sharp cognitive decline and lost the ability to communicate, his eyes opening only in response to painful stimuli. His palliative-care team deemed him incapable of consenting to health-care decisions, including final permission for MAID. Despite that conclusion, a MAID clinician proceeded with the assessment, “vigorously” rousing the man to ask if he still wanted euthanasia (to which the man mouthed “yes”), and then withholding the man’s pain medication until he appeared “more alert.” After confirming the man’s wishes via “short verbal statements” and “head nods and blinking,” the assessor approved him for MAID; with sign-off from a second clinician, and a final consent from Mr. C mouthing “yes,” he was euthanized.

Had this patient clearly consented to his death? Finding no documentation of a “rigorous evaluation of capacity,” the death-review committee expressed “concerns” about the process. The implication would seem startling—in a regime animated at its core by patient autonomy, a man was not credibly found to have exercised his own. Yet Mr. C’s death was reduced essentially to a matter of academic inquiry, an opportunity for “lessons learned.” Of the hundreds of irregularities flagged over the years by the coroner’s office, almost all have been dealt with through an “Informal Conversation,” an “Educational Email,” or a “Notice Email,” depending on their severity. Specific sanctions are not made public. No case has ever been referred to law enforcement for investigation.

Wiebe acknowledged that several complaints have been filed against her over the years but noted that she has never been found guilty of wrongdoing. “And if a lawyer says, ‘Oh—I disagreed with some of those things,’ I’d say, ‘Well, they didn’t put lawyers in charge of this.’ ” She laughed. “We were the ones trusted with the safeguards.” And the law was clear, Wiebe said: “If the assessor”—meaning herself—“believes that they qualify, then I’m not guilty of a crime.”

Despite all of the questions surrounding Track 2, Canada is proceeding with the expansion of MAID to additional categories of patients while gauging public interest in even more. As early as 2016, the federal government had agreed to launch exploratory investigations into the possible future provision of MAID for people whose sole underlying medical condition is a mental disorder, as well as to “mature minors,” people younger than 18 who are “deemed to have requisite decision-making capacity.” The government also pledged to consider “advance requests”—that is, allowing people to consent now to receive MAID at some specified future point when their illness renders them incapable of making or affirming the decision to die. Meanwhile, the Quebec College of Physicians has raised the possibility of legalizing euthanasia for infants born with “severe malformations,” a rare practice currently legal only in the Netherlands, the first country to adopt it since Nazi Germany did so in 1939.

As part of Track 2 legislation in 2021, lawmakers extended eligibility—to take effect at some point in the future—to Canadians suffering from mental illness alone. This, despite the submissions of many of the nation’s top psychiatric and mental-health organizations that no evidence-based standard exists for determining whether a psychiatric condition is irremediable. A number of experts also shared concerns about whether it was possible to credibly distinguish between suicidal ideation and a desire for MAID.

After several contentious delays, MAID for mental illness is now set to take effect in 2027; authorities have been tasked in the meantime with figuring out how MAID should actually be applied in such cases. The debate has produced thousands of pages of special reports and parliamentary testimony. What all sides do agree on is that, in practice, mental disorders are already a regular feature of Canada’s MAID regime. At one hearing, Mona Gupta, a psychiatrist and the chair of an expert panel charged with recommending protocols and safeguards for psychiatric MAID, noted pointedly that “people with mental disorders are requesting and accessing MAID now.” They include patients whose requests are “largely motivated by their mental disorder but who happen to have another qualifying condition,” as well as those with “long histories of suicidality” or questionable decision-making capacity. They may also be poor and homeless and have little interaction with the health-care system. But whatever the case, Gupta said, when it comes to navigating the complex intersection of MAID and mental illness, “assessors and health-care providers already do this.”

The argument was meant to assuage concerns about clinical readiness. For critics, however, it only reinforced a belief that, in some cases, physical conditions are simply being used to bear the legal weight of a different, ineligible basis for MAID, including mental disorders. In one of Canada’s more controversial cases, a 61-year-old man named Alan Nichols, who had a history of depression and other conditions, applied for MAID in 2019 while on suicide watch at a British Columbia hospital. A few weeks later, he was euthanized on the basis of “hearing loss.”

[Read: ‘I’m the doctor who is here to help you die’]

As Canadians await the rollout of psychiatric MAID, Parliament’s Special Joint Committee on Medical Assistance in Dying has formally recommended expanding MAID access to mature minors. In the committee’s 2023 report, following a series of hearings, lawmakers acknowledged the various factors that could affect young people’s capacity to evaluate their circumstances—for one, the adolescent brain’s far from fully developed faculties for “risk assessment and decision-making.” But they noted that, according to several parliamentary witnesses, children with serious medical conditions “tend to possess an uncommon level of maturity.” The committee advised that MAID be limited (“at this stage”) to minors with reasonably foreseeable natural deaths, and endorsed a requirement for “parental consultation,” but not parental consent. As a lawyer with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Saskatchewan told the committee, “Parents may be reluctant to consent to the death of their child.”

Whether Canadian officials will eventually add mature minors to the eligibility list remains unclear. At the moment, their attention is largely focused on a different category of expansion. Last year, the province of Quebec took the next step in what some regard as the “natural evolution” of MAID: the honoring of advance requests to be euthanized. Under the Quebec law, patients in the province with cognitive conditions such as Alzheimer’s can define a threshold they don’t wish to cross. Some people might request to die when they no longer recognize their children, for example; others might indicate incontinence as a benchmark. When the threshold seems to have been reached, perhaps after an alert from a “trusted third party,” a MAID practitioner determines whether the patient is indeed suffering intolerably according to the terms of the advance request. Since 2016, public demand for this expansion has been steady, fueled by the testimonies of those who have watched loved ones endure the full course of dementia and do not want to suffer the same fate.

In parliamentary hearings, Quebec officials have discussed the potential problem of “pleasant dementia,” acknowledging that it might be difficult for a provider to euthanize someone who “seems happy” and “absolutely doesn’t remember” consenting to an assisted death earlier in their illness. Quebec officials have also discussed the issue of resistance. The Netherlands, the only other jurisdiction where euthanizing an incapable but conscious person as a result of an advance request is legal, offers an example of what MAID in such a circumstance could look like.

In 2016, a geriatrician in the Netherlands euthanized an elderly woman with Alzheimer’s who, four years earlier, shortly after being diagnosed, had advised that she wanted to die when she was “no longer able to live at home.” Eventually, the woman was admitted to a nursing home, and her husband duly asked the facility’s geriatrician to initiate MAID. The geriatrician, along with two other doctors, agreed that the woman was “suffering hopelessly and intolerably.” On the day of the euthanasia, the geriatrician decided to add a sedative surreptitiously to the woman’s coffee; it was given to “prevent a struggle,” the doctor would later explain, and surreptitiously because the woman would have “asked questions” and “refused to take it.” But as the injections began, the woman reacted and tried to sit up. Her family helped hold her down until the procedure was over and she was dead. The case prompted the first criminal investigation under the country’s euthanasia law. The physician was acquitted by a district court in 2019, and that decision was upheld by the Dutch supreme court the following year.

In Quebec, more than 100 advance requests have been filed; according to several sources, at least one has been carried out. The law currently states that any sign of refusal “must be respected”; at the same time, if the clinician determines that expressions of resistance are “behavioural symptoms” of a patient’s illness, and not necessarily an actual objection to receiving MAID, the euthanasia can continue anyway. The Canadian Association of MAiD Assessors and Providers has stated that “pre-sedating the person with medications such as benzodiazepines may be warranted to avoid potential behaviours that may result from misunderstanding.”

Laurent Boisvert, an emergency physician in Montreal who has euthanized some 600 people since 2015, told me that he has thus far helped seven patients, recently diagnosed with Alzheimer’s, to file advance requests, and that they included clear instructions on what he is to do in the event of resistance. He is not concerned about potentially encountering happy dementia. “It doesn’t exist,” he said.

The Canadian government had tried, in the early years of MAID, to forecast the country’s demand for assisted death. The first projection, in 2018, was that Canada’s MAID rate would achieve a “steady state” of 2 percent of total deaths; then, in 2022, federal officials estimated that the rate would stabilize at 4 percent by 2033. After Canada blew past both numbers—the latter, 11 years ahead of schedule—officials simply stopped publishing predictions.

And yet it was never clear how Canadians were meant to understand their country’s assisted-death rate: whether, in the government’s view, there is such a thing as too much MAID. In parliamentary hearings, federal officials have indicated that a national rate of 7 percent—the rate already reached in Quebec—might be potentially “concerning” and “wise and prudent to look into,” but did not elaborate further. If Canadian leaders feel viscerally troubled by a certain prevalence of euthanasia, they seem reluctant to explain why.

The original assumption was that euthanasia in Canada would follow roughly the same trajectory that euthanasia had followed in Belgium and the Netherlands. But even under those permissive regimes, the law requires that patients exhaust all available treatment options before seeking euthanasia. In Canada, where ensuring access has always been paramount, such a requirement was thought to be too much of an infringement on patient autonomy. Although Track 2 requires that patients be informed of possible alternative means of alleviating their suffering, it does not require that those options actually be made available. Last year, the Quebec government announced plans to spend nearly $1 million on a study of why so many people in the province are choosing to die by euthanasia. The announcement came shortly after Michel Bureau, who heads Quebec’s MAID-oversight committee, expressed concern that assisted death is no longer viewed as an option of last resort. But had it ever been?

It doesn’t feel quite right to say that Canada slid down a slippery slope, because keeping off the slope never seems to have been the priority. But on one point Etienne Montero, the former head of the European Institute of Bioethics, was correct: When autonomy is entrenched as the guiding principle, exclusions and safeguards eventually begin to seem arbitrary and even cruel. This is the tension inherent in the euthanasia debate, the reason why the practice, once set in motion, becomes exceedingly difficult to restrain. As Canada’s former Liberal Senate leader James Cowan once put it: “How can we turn away and ignore the pleas of suffering Canadians?”

In the end, the most meaningful guardrails on MAID may well turn out to be the providers themselves. Legislative will has generally been fixed in the direction of more; public opinion flickers in response to specific issues, but so far remains largely settled. If MAID reaches a limit in Canada, it will happen only when practitioners decide what they can tolerate—morally or, in a system with a shrinking supply of providers, logistically. “You cannot ask us to provide at the rate we’re providing right now,” Claude Rivard, who has decided not to accept advance requests, told me. “The limit will always be the evaluation and the provider. It will rest with them. They will have to do the evaluation, and they will have to say, ‘No, it’s not acceptable.’”

Lori Verigin, a nurse practitioner who provides euthanasia in rural British Columbia, understands that people are concerned about their “rights”—about “not being heard.” Yet she is the person on the line when it comes to ensuring those rights. This is what is often lost in Canada’s conversation about assisted dying—about the push for expansion in the academic papers or in the rarefied halls of Parliament. It is not the lawmaker or lawyer or pundit who must administer an injection and stop a heart.

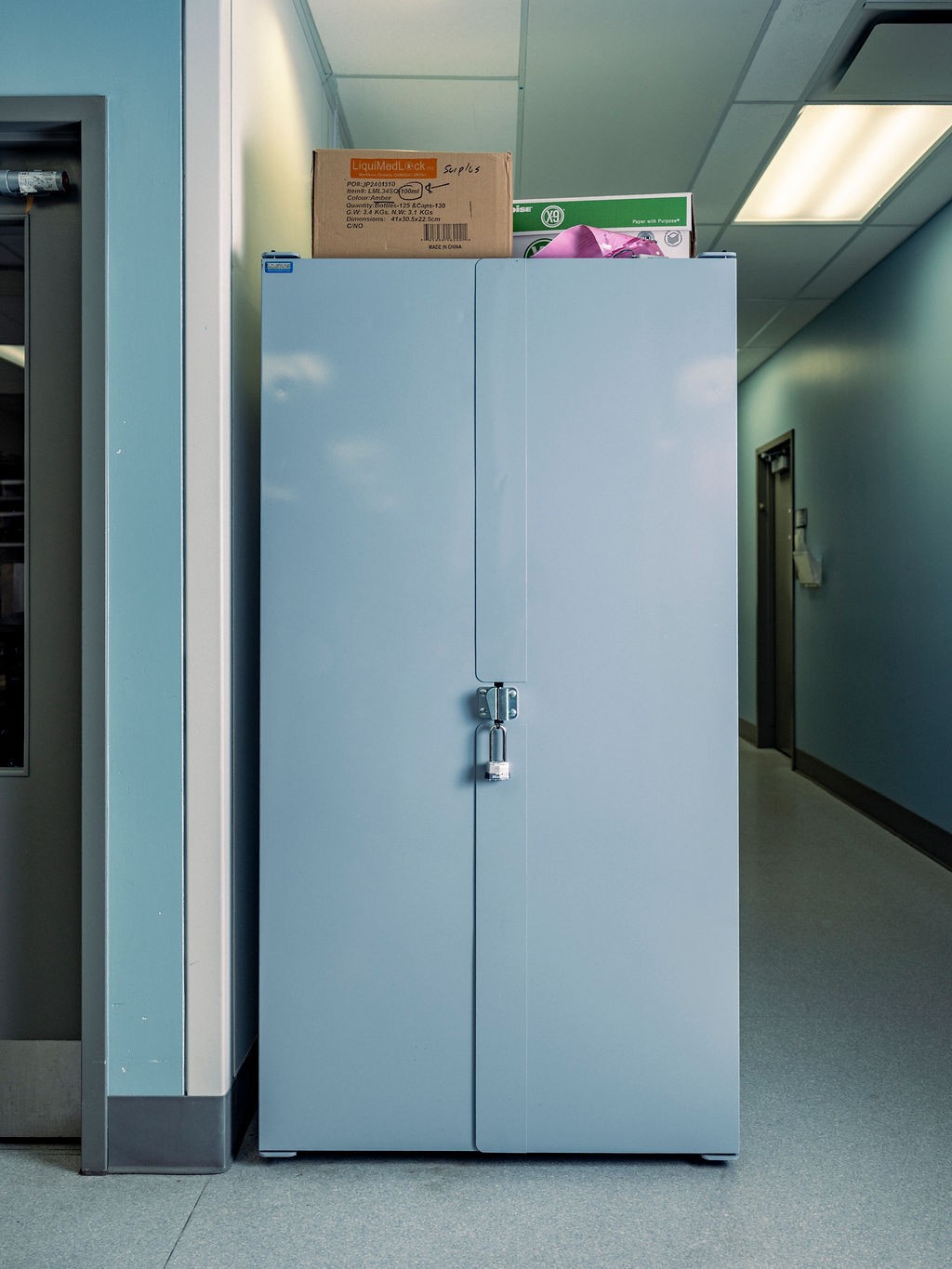

On a Thursday morning in June, I joined Verigin in her white Volkswagen as she drove to a MAID appointment near the town of Trail. I had not come to witness the provision, to be a stranger in the room. I was with Verigin because I wanted to understand the before-and-after of MAID, the clinical and emotional labor involved in helping someone die. After eight years, Verigin had developed a familiar set of rhythms. She had her preferred pharmacy, the Shoppers Drug Mart close to her home, in Castlegar. This morning she had arrived as the doors opened, prescription in hand; the pharmacist greeted her by name before placing on the counter a medium-size case resembling a tackle box. Verigin unsnapped the lid and confirmed that everything was in place: the vials of midazolam, lidocaine, propofol, and rocuronium.

Verigin had known the patient she was about to visit for some time, she told me. Roughly a year ago, the patient, suffering from metastatic cancer, had first asked about MAID; two weeks earlier, the patient had looked at her and said: “I’m just done.” Verigin sipped from a to-go cup of coffee, decaf, as she drove. “I try not to have too much caffeine before,” she said.

En route to the patient’s home, we stopped by the hospital to pick up Beth, an oncology nurse who often assists Verigin. Beth has a gift for assessing the energy of the room, Verigin told me, knowing when someone suddenly needed a hand held or a Kleenex, thus allowing Verigin to fully focus on the injections. Beth’s mother, Ruth, had also helped solve a problem Verigin had experienced early in her MAID practice—how obtrusive it felt rolling a clattering tray of syringes into the already fragile atmosphere of a patient’s home. A quilter, Ruth had designed a soft pouch with syringe inserts that rolled up like a towel. The fabric was tie-dyed and the soft bundle was secured with a Velcro strap.

We parked outside the patient’s ranch-style home, the white sun glaring in a clear sky. At exactly 10 a.m., the two clinicians walked to the door, where moments later they were greeted by one of the patient’s grown children. The door clicked faintly behind them.

I remained in the car, and for the next while watched the slow turn of other Thursdays: the neighbors across the street chatting in their sunroom, a dog lazing in front of a box fan. Then, at 11:39 a.m., a text message from Verigin: “We’re done.”

The clinicians were quiet as they slid into the car. “Things weren’t as predictable today,” Verigin said finally. Finding a vein had been unusually hard, and they worried momentarily that they might not succeed, at one point leaving the room to discuss their options. “It’s always been a challenge,” the patient had reassured Beth. “You’re very gentle. It’s not hurting.” The patient had remained calm, unfazed. “I’m sure they were doing that for the kids, to be honest,” Beth said. “And probably me too.”

Once the IV was in place, the provision had unfolded as planned: midazolam, lidocaine, propofol, rocuronium, death. Afterward, the family had thanked and hugged the clinicians. “I think the end outcome was good,” Verigin said. “I probably would be feeling different if we couldn’t fulfill the patient’s wish, because it’s also that big buildup and the anticipation.”

Verigin described a checklist of follow-up tasks, including the paperwork that has to be submitted within 72 hours. But for the rest of the day, her duties as a nurse practitioner would take priority. Only later that night, she said, would she finally have the space to reflect on the events of the morning. When the syringes and vials have been packed up, and the goodbyes to the survivors have been said, it is Lori Verigin who sits in her garden alone. “We are not just robots out there—we’re human beings,” she said. “And there has to be some respect and acknowledgment for that.” Verigin told me she never wants to feel “comfortable” providing assistance in dying. The day she did, she said, would be the day she knew to step back.

For Verigin, providing MAID to Track 1 patients and even to some Track 2 patients has “felt sensible.” She explained: “Yes, I may be nervous. Yes, I may be sad. Yes, I may have a lot of, you know, emotions around it, but I feel like it’s the right thing.” But when it comes to minors, or patients solely with mental disorders, or patients making advance requests, “I don’t know if I’ll feel that way.”

After dropping Beth off at the hospital in Trail, Verigin headed to the Shoppers Drug Mart in Castlegar to return the tackle box. Verigin told the pharmacist she would be back on June 18—the date of her next provision. The pharmacist was grateful for the notice. She would go ahead and order the propofol.

This article appears in the September 2025 print edition with the headline “Canada Is Killing Itself.”