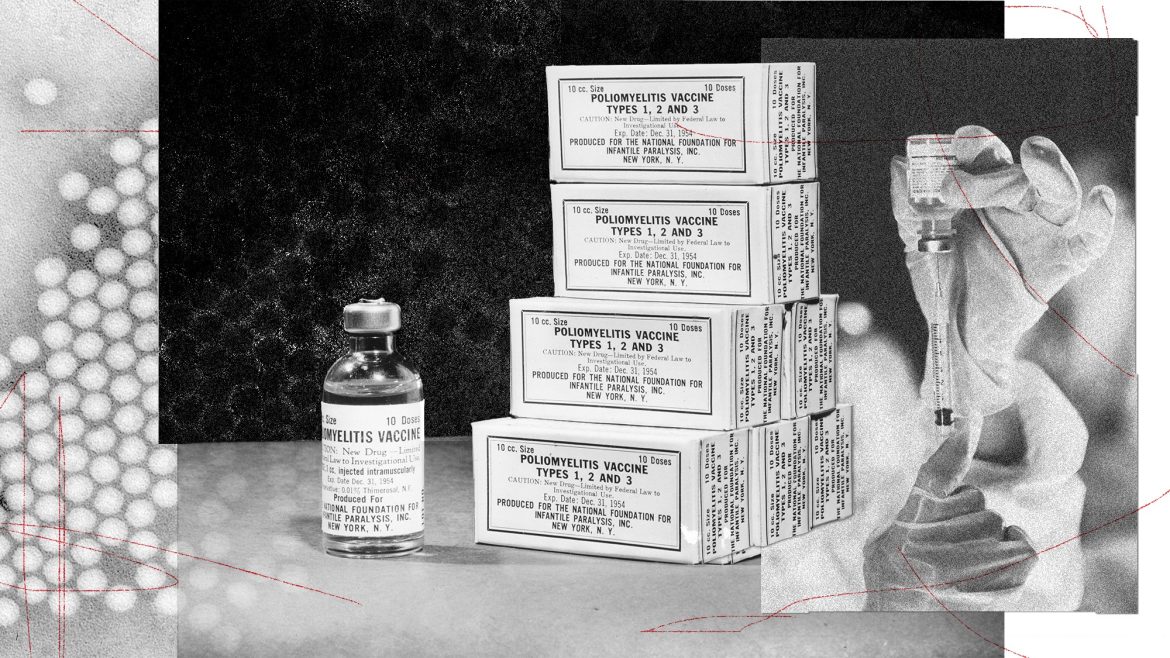

In the United States, polio is a memory, and a fading one at that. The last major outbreak here happened in 1952; the virus was declared eliminated in 1979. With all of that behind us, you can see how someone—say, Kirk Milhoan, the chair of the CDC’s vaccine advisory committee—might wonder whether giving the polio vaccine to American kids still makes sense. “We need to not be afraid to consider that we are in a different time now,” Milhoan said on the podcast Why Should I Trust You? last week.

To be fair, Milhoan didn’t endorse yanking the polio vaccine from the CDC’s childhood-immunization schedule, as other vaccines were earlier this month. But he didn’t rule it out. And right now, when it comes to vaccines in America, anything seems possible. With Robert F. Kennedy Jr. at the helm of the Department of Health and Human Services, and with the CDC’s vaccine advisory committee stacked with his allies, every inoculation—no matter how well studied or successful—seems to be under new scrutiny, and at least potentially on the chopping block. Next on the committee’s agenda is looking into the safety of aluminum salts, which are used in numerous vaccines to boost the recipient’s immune response. For the record, a study of more than 1 million Danish children, published last July, found no statistically significant evidence linking aluminum in vaccines to asthma, autoimmune conditions, or neurodevelopmental disorders, including autism.

The polio vaccine, which doesn’t contain aluminum, hasn’t received much attention so far from Kennedy’s HHS; the department did not respond to my questions about whether it is considering changing its recommendations about this vaccine, and my queries to Milhoan went unanswered. But its time may be coming. As anti-vaccine activists are quick to point out, an American kid’s risk of catching polio in 2026 is vanishingly low. So why don’t we drop it from the recommendation list? Or perhaps, as we did with the smallpox vaccine in the early 1970s, just stop offering it altogether?

In anti-vaccine circles, the official story of polio—iron lungs, kids with leg braces, the triumph of Jonas Salk—has long been dismissed as misleading. In a 2020 debate with the lawyer Alan Dershowitz, Kennedy raised doubts about whether the vaccine had really been responsible for ridding the country of polio, crediting instead factors such as sanitation and hygiene. Last June, Aaron Siri, a lawyer who has worked closely with Kennedy, called for the polio vaccine to be struck from the CDC’s recommendations. In his recent book, Vaccines, Amen, Siri argues that the seriousness of polio has been overblown—a sentiment shared by others in the health secretary’s orbit, including Del Bigtree, who served as the communications director for Kennedy’s presidential campaign. Joe Rogan suggested on his podcast last March that the pesticide DDT, rather than the virus, deserved blame for symptoms attributed to polio.

[Read: Here’s how we know RFK Jr. is wrong about vaccines]

That’s all nonsense. Polio, which usually spreads through contact with an infected person’s feces via contaminated hands or water, can be a devastating disease. That 1952 outbreak killed some 3,000 people and left more than 20,000 paralyzed. About one in 200 people who contract polio will experience a form of paralysis. As many as 40 percent of people who recover from the virus, even a mild form of it, develop post-polio syndrome, which can emerge decades after an infection and cause weakened muscles and trouble breathing and swallowing. The vaccines—the original shot that contains inactivated-virus particles, plus an oral solution of weakened live viruses—did indeed lead to the near-elimination of polio globally and has spared millions from the worst outcomes of the disease.

Yet polio has proved stubbornly hard to stamp out. In 1988, as the virus was still endemic to more than 100 countries, the World Health Organization set a goal to eradicate polio by the year 2000. That deadline came and went, as did the ones that followed. A wild strain of the virus remains endemic in Pakistan and Afghanistan, and periodic outbreaks continue across Africa and elsewhere, including one in the Gaza Strip in 2024. One obstacle to eradicating the virus has been vaccine hesitancy, and even violence against health workers. In the early 2000s, five states in northern Nigeria boycotted the polio vaccine in part because of rumors that it was an American plot to spread HIV. Polio workers have been killed in Pakistan and Afghanistan, likely by the Taliban, which has alleged that vaccines are intended to sterilize Muslim children (and has denied responsibility for some of the attacks).

In regions where polio is rampant, the oral vaccine is preferred: It’s both cheaper and more effective at stopping transmission than the inactivated-virus injection. The United States and other countries where the disease is almost nonexistent exclusively use the inactivated version—in part because in rare instances, the oral vaccine can cause polio infection, which may in turn lead to paralysis. Anti-vaccine activists like to point to this unfortunate irony as proof that vaccination is the real villain. Taking the oral vaccine remains far less risky than contracting the wild virus, and it has driven down overall infection rates. But it’s an imperfect tool, and the WHO intends to phase it out by the end of 2029. (Given historical precedent, along with the Trump administration’s dramatic pullback from polio-vaccination efforts as part of its dismantling of foreign aid, this timeline might be optimistic.)

[Read: Polio is exploiting a very human weakness]

Ending polio vaccination altogether, according to the WHO’s plan, will take considerably longer. After polio is declared eradicated worldwide, the organization wants countries to wait 10 years before stopping use of the inactivated-virus shots to be certain that it is no longer circulating, Oliver Rosenbaum, a spokesperson for WHO’s Global Polio Eradication Initiative, told me.

Some polio experts, though, told me that they think ending vaccination at any point is unrealistic. Because in many cases the disease spreads without a person showing symptoms (unlike smallpox, which is not contagious before symptoms develop), large numbers of people can be infected before authorities are even aware of an outbreak. Some experts, such as Konstantin Chumakov, a virologist who began researching polio in 1989, worry that the virus could be used as a biological weapon in an entirely unvaccinated country. “In my opinion, and in the opinion of many respected polio experts, this is absolutely unacceptable because you can never assure that polio is completely eradicated,” Chumakov told me.

Ending or reducing polio vaccination in the U.S. before global eradication, as Milhoan seems to imply the country should consider, would be an even worse idea. A paper published last April in the Journal of the American Medical Association projected the consequences of U.S. vaccination rates declining by half and concluded that the country would see a significant return of paralytic polio. Some paralyzed people would probably require a ventilator, the modern equivalent of the iron lung, and, based on typical fatality rates, about 5 to 10 percent of them would die.

If Americans stopped vaccinating their kids against polio entirely, several years might pass without the U.S. having any cases, or with it seeing just a few here and there, Kimberly Thompson, a public-health researcher and the president of the research nonprofit Kid Risk, told me. (Even under the current vaccination system, occasional spread of the virus occurs. In 2022, for instance, an unvaccinated young adult in Rockland County, just north of New York City, tested positive for a vaccine-derived strain of polio even though they hadn’t traveled overseas.) But eventually, we could find ourselves back in the same situation as in the early 1950s.

Or it could be even worse. Seventy-five years ago, many American children inherited some polio immunity from their mother, and so they had at least partial protection against the virus’s worst effects. The introduction of polio to a population that has little to no immunity could cause its mortality rates to exceed those experienced in the first half of the previous century, Chumakov said. A 2021 study, co-authored by Thompson, modeled what might happen in an extreme scenario: if global polio vaccination ended, no one were immune, and the virus had somehow been reintroduced. It estimates that such a scenario could cause tens of millions of cases of paralysis worldwide.

[Read: South Carolina is America’s new measles norm]

Milhoan insisted on the podcast that Americans shouldn’t be afraid to rethink vaccine policy. And he’s right that health authorities should reevaluate risk and offer the most up-to-date medical advice. Still, there’s something to be said for the utility of fear. Most Americans, including me, are too young to have any personal knowledge of polio. It’s all textbook summaries and black-and-white newsreels; we’ve never worried about shaking someone’s hand or going swimming and then ending up in a wheelchair. But vaccines are the only thing stopping us from getting another firsthand look.